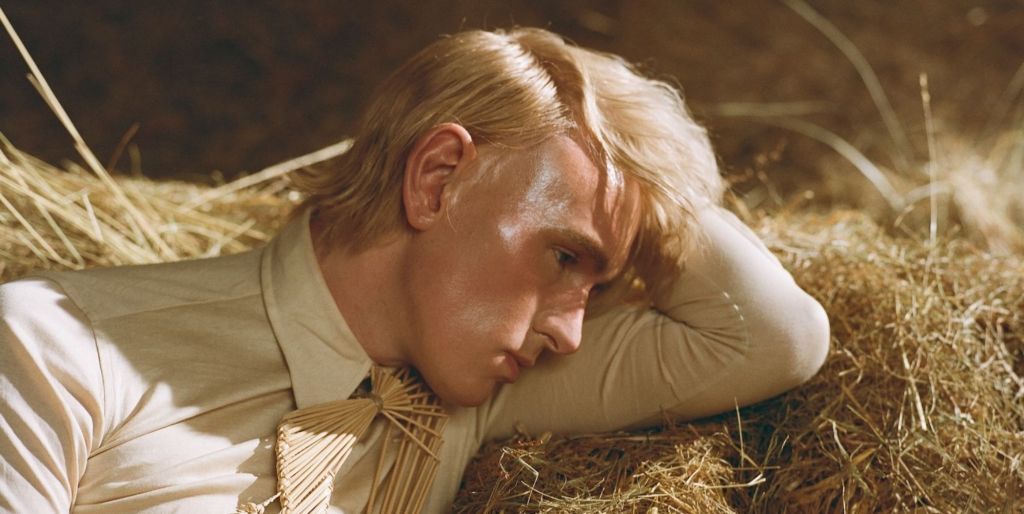

It’s been 13 tumultous years since Patrick Wolf released an album. Now, he’s back. (Furmaan Ahmed)

A cursory Google of singer-songwriter Patrick Wolf will offer the first suggested query: “What happened to Patrick Wolf?”

“I find that so hilarious,” beams Patrick Wolf, a supposedly missing man, yet sat staring at me in an off-white vest top with slicked back bleach blonde hair via Zoom from his home on the Kent coast, where he moved post lockdown. “Not even I really understand what happened just yet.”

It turns out that a lot happened to Patick Wolf, born Patrick Apps, in the 13 years since he released his last album, Sundark and Riverlight. “Do you know that Katie Price meme that goes around all the time?” he asks, the one where she’s on This Morning talking at speed about being held at gunpoint in South Africa, her German Shepherd being killed on her driveway, and her horse being killed on a dual carriageway. “Sometimes I feel like that when I talk about those 10 years,” Wolf says, eyes widening, still smiling.

Wolf, now 41, was 29 years-old when he released Sundark and Riverlight, a double disc album featuring re-records of his previous songs. By that point, before he’d even brushed 30, he’d released six records and built a reputation as one of the UK’s most gloriously unplaceable musical oddities. Then the wheels fell off spectacularly.

First came creative burnout after a move to major labels for his third and fifth albums, The Magic Position and Lupercalia, which were “made under quite a lot of pressure and tug of war between A&R people” who struggled to find a musical “hole that they could stuff me through, basically,” says Wolf. An addiction to drugs and alcohol persisted. In 2015, he was seriously injured in a hit-and-run in Italy; the same month his mother, artist Imelda Apps, was diagnosed with angiosarcoma cancer. In 2017 he was declared bankrupt due to tax neglect by his former management, and in 2018, as he slowly awoke to the idea of making a new record, Imelda died, and he relapsed.

If his 2023 EP The Night Safari was a reflection on an impossible decade, then his new record Crying The Neck, due for release in June, is an exorcism.

The title itself is derived from a harvest tradition once common in Cornwall and Devon, whereby farmers would hold up the final neck of corn and chant, signalling the end of harvest. Wolf – an avid collector of mythology books – came across the concept in a folklore encyclopedia.

“When I first saw it on the page it made me think of actually the primal cry that you make when in grief, when you’ve lost something so shocking, that you’re not crying up here, you’re crying down here,” he says, drifting fingers from his eyes to his throat. It was the type of guttural wailing he would hear in the family home in the months following his mother’s death.

“And then, the end of the harvest. In a way, my mother’s death was the end of many miserable events in my life. Her death signalled the end of the first chapter of my life, really. I had to rebuild my life from there. For me, that was the changing point. The changing of the season was her.”

The album’s first single “Dies Irae” is a musing on his mother’s passing, but not through a lens of blistering heartache. “I was really trying so hard to keep the Grim Reaper out of it,” he says; the word “death” appears just once on the album. Over blustering percussion and cascading strings, Wolf reimagines one more day in his mother’s studio in her garden, as the sun goes down on their time together. “Take this moment, you’ll always have home in it, the time is here,” he coos, rounding off a song that is strangely more anthemic than funeral dirge.

Similar surprisingly bright soundtracks to life-shifting grief are found elsewhere on the record, such as the buoyant “Better of Worse”, which references the East Kent folk custom of ‘hoodening’ in which a wooden horse dies and is resurrected for performance, and “Better or Worse”, which was written on Wolf’s first visits to the hospital to see his mother, and is now set to the sweet strings of the Appalachian Dulcimer.

“When I cry about somebody that I know that has died, it’s generally because I’m thinking of something about them that was beautiful. It’s a beautiful afternoon, it’s a conversation that uplifted you,” Wolf explains, softly. He considers the things his mother gave him, material or otherwise. Perched on the back of his burnt orange sofa are three of her paintings, framing him. He wonders if we should recognise an additional stage of grief: a state of joy, where you’re able to appreciate all that a person brought to the world and all that they left. “I think it was really important to kind of investigate the sublime aspect of grief.”

Wolf relays this period with contemplative stoicism, but it’s clearly, and understandably, still hard. “How am I? That would probably take a long time to answer. It’s not an easy question for me,” is how he begins our call, though with a knowing smile and a shuffling of his camera, settling into the discomfort. He’s sometimes a little uncertain with his words, but he’s grateful he has any. On the swirling, piano-and-strings hymn “The Curfew Bell” he trills about words leaving him during his grief. “I think what I ended up doing on the album is just about as many words as I could get on the subject. For like two, three years, I had absolutely no way of writing about what had just happened. My family had no way of talking about it,” he says.

His move to Ramsgate from London in 2020 was transformative. He was jaded by the rhythms of London living, where “things get knocked down, things get built, and you see things come and go… I get incredibly bored there”. Having just got both clean and sober, he needed to find a sense of enchantment to fill the void. “I’m sorry, but like on the eighth floor of a miserable tower block in Sydenham, I had like zero wonder,” he deadpans, suggesting that the recesses of Lewisham did nothing to aid his recovery. A true Cancerean (he was born on 30 June, 1983), he headed to the sea to find fascination. “If I feel at my completely most nihilistic and just want a bomb to drop on the UK, all I have to do is drive to Dover,” he says, “and the insanity just completely disappears when I’m on the White Cliffs. It’s just that feeling of the insignificance of your of your misery, really.”

He built a studio in his garden, and inspiration crashed down like the waves he watched. Four, maybe five, albums have materialised and will be released. He begins the new phase of his career by sending up the old. Crying The Neck’s opener “Reculver” offers some of his most acerbic songwriting yet: “Bankrupt and borderline, orphaned and obsolete. Well, enough of my accomplishments: here’s to the bridges burnt, never to mend.”

The song felt like a “triumph” in Wolf’s bid to move away from victimhood, to own the last decade with a sense of humour. “I do take responsibility. You have to as an addict and an alcoholic have to start taking responsibility for things which you blame people for for years. I think it’s a really liberating experience.” Finishing the song – which he first started aged 16 – gave him the jumpstart he needed to pull the record together, pushing him to realise that he “never lost love or passion. I lost faith in what I could do, but I never lost the the fire for doing this work”.

“Reculver” also satirises those Google searches about his whereabouts: “How many years can you disappear for before they call off the patrol?” he questions on the soaring chorus. With every year that passed, he increasingly wondered whether he had been “declared dead” by his audience. Yet a reintroduction tour in 2023, which saw him trekking across Europe with viola in hand, blew his expectations out of the water. Another pre-album tour is happening now. His fans had been eagerly anticipating his return, like a musical Jesus. “I feel like Maria Callas in Italy, you know,” he twinkles. “I get treated like a diva there.”

Looking out into the audiences he could see, to his surprise, homosexuals. He suggests that since his commercial apex, gay men have been “allowed to go to more experimental places” musically. I wonder if that wasn’t always the case, but he has more reason than most to believe that gay men have been culturally boxed in by the mainstream. “In 2007, gayness, musically, meant gay people like Steps, or Scooch, or Eurovision, or Kylie. If you’re thinking about from a marketing perspective, gayness meant quite superficial, fluffy things,” he says.

As a gay musician who didn’t make cookie-cutter pop, the industry viewed Wolf as something of an iconoclast. The media emphasised his “flamboyancy”; the major labels he signed with didn’t know what to make of him. There was pressure for him to inch further into the mainstream, “which is the reason why I got dropped, was because I refused to change the sound after The Magic Position, because they realised it wasn’t working”.

Indie spaces weren’t exactly welcoming, either. “There was a sense of, of course, sexism, racism and homophobia back then. It was a white straight, white boys world,” he says, though he is sanguine. “In any field that I was working in, I didn’t belong there, and I’m fine with that and I was fine with it at the time. There was a feeling of ostracisation probably from all sides of the media but I’m very happy I provided counter culture at the time.”

On “Oozlum” from the new record, Wolf warns that if you “stare at the past too long, to there you’ll disappear”. Looking back all the time doesn’t feel healthy. It feels good to tear up the annals a little and move forward. Yet despite his troubled decade and fractured relationship with his early career, he’s proud.

“I’m quite astonished actually when I think about my position within the music industry, of being such an oddity and a loner, that I was so nonchalant about the whole thing. Irreverent, really,” he says.

“I could never do what I did in 2007 now, I’m far too private and I have far too many boundaries now, and very protective of the life that I have and the sanity that I have. So I look back at that in terms of what I had to do, in terms of being public facing, as incredibly brave.”

Crying The Neck is out on 13 June. Patrick Wolf is touring the UK and Europe until June. Tickets are available now.

Share your thoughts! Let us know in the comments below, and remember to keep the conversation respectful.

How did this story make you feel?