Corporate Climate Disclosures and Practices: Risk, Emissions, and Targets

As climate risks intensify, more companies are embedding emissions reduction and climate governance into core strategy. This report analyzes 2021–2024 climate disclosures across the Russell 3000 and S&P 500, highlighting trends in greenhouse gas (GHG) reporting, target setting, regulatory preparedness, and board oversight. While based in the US, many firms—especially those in the S&P 500—operate globally under multiple regulatory regimes.

Key Insights

- Most US public companies now disclose their exposure to climate risk—especially in assetheavy, high-exposure sectors—although not all deem it to be financially material.

- Despite a US federal shift away from climate regulation, emerging state disclosure laws like California’s Senate Bill (SB) 261 and international mandates such as in the EU will likely reinforce climate risk and reporting as a board-level issue for large US companies.

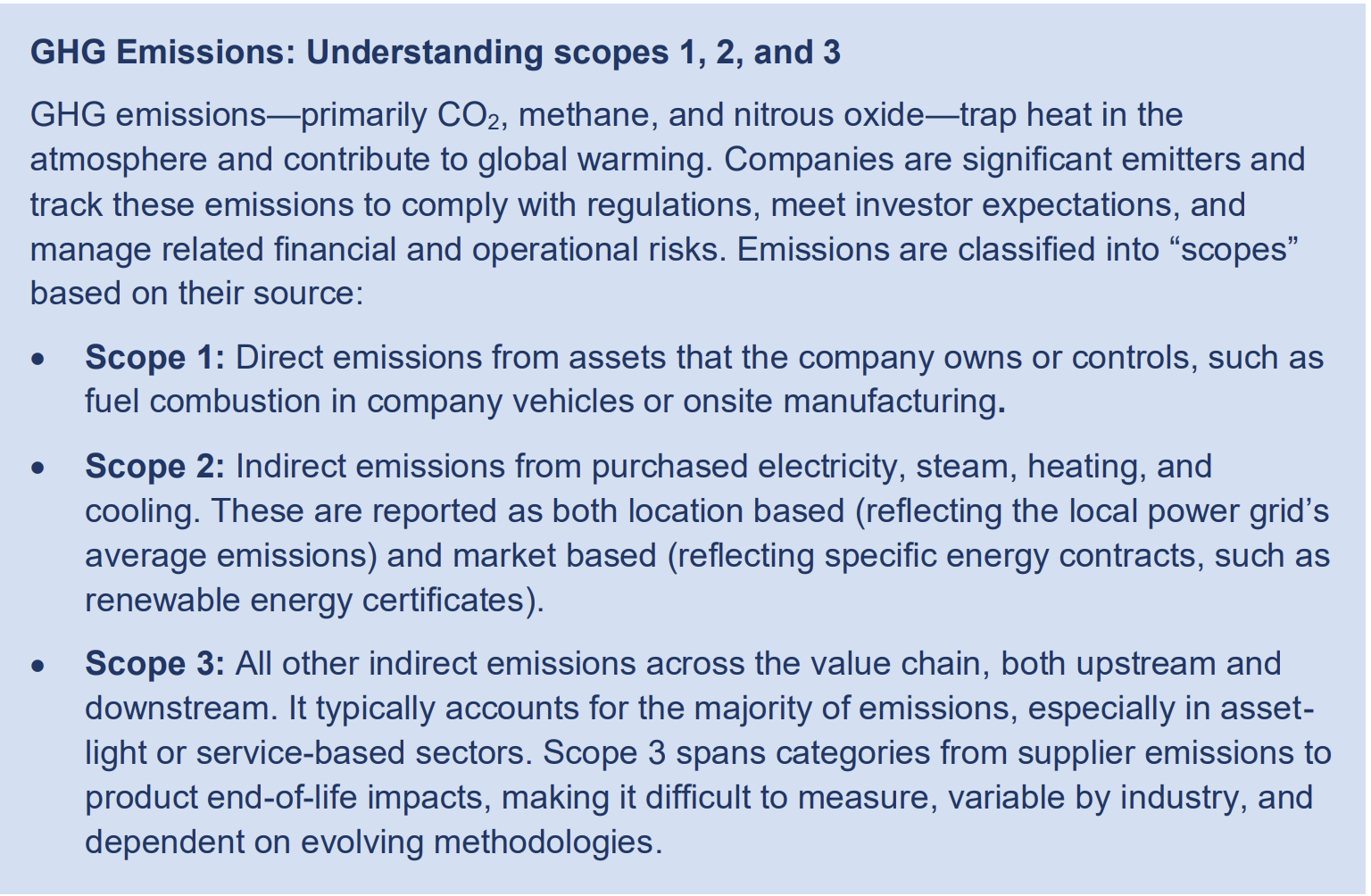

- US public companies have increased disclosures and made tangible progress on reducing scope 1 (direct) and scope 2 (indirect) GHG emissions, due largely to operational efficiency improvements, renewable energy purchases, and grid decarbonization.

- Scope 3 (value chain) emission disclosure is increasing, particularly among large-cap firms, though progress is mixed and data limits persist. Companies can plan ahead by engaging key suppliers, enhancing data quality, and using external assurance to ensure integrity.

- Most large US companies have set public climate targets—such as becoming carbon neutral by 2030—but the pace of new goals has slowed amid feasibility and reputational challenges.

Climate Risk Disclosure and Management

Climate Risk Disclosure and Management

Climate risk encompasses the financial, operational, and strategic threats posed by climateinduced events—including both physical risks (e.g., extreme weather, sea level rise, and water scarcity) and transition risks (e.g., regulatory shifts, carbon pricing, and investor expectations). As weather events become more severe and costly, the risk level increases: in 2024 alone, the US experienced 27 weather and climate disasters exceeding $1 billion in damages—more than double the annual average of the prior decade. Operational disruptions from these events are growing, with examples ranging from weather-related shutdowns in auto manufacturing to home insurance providers retreating from markets prone to floods, wildfires, and hurricanes.

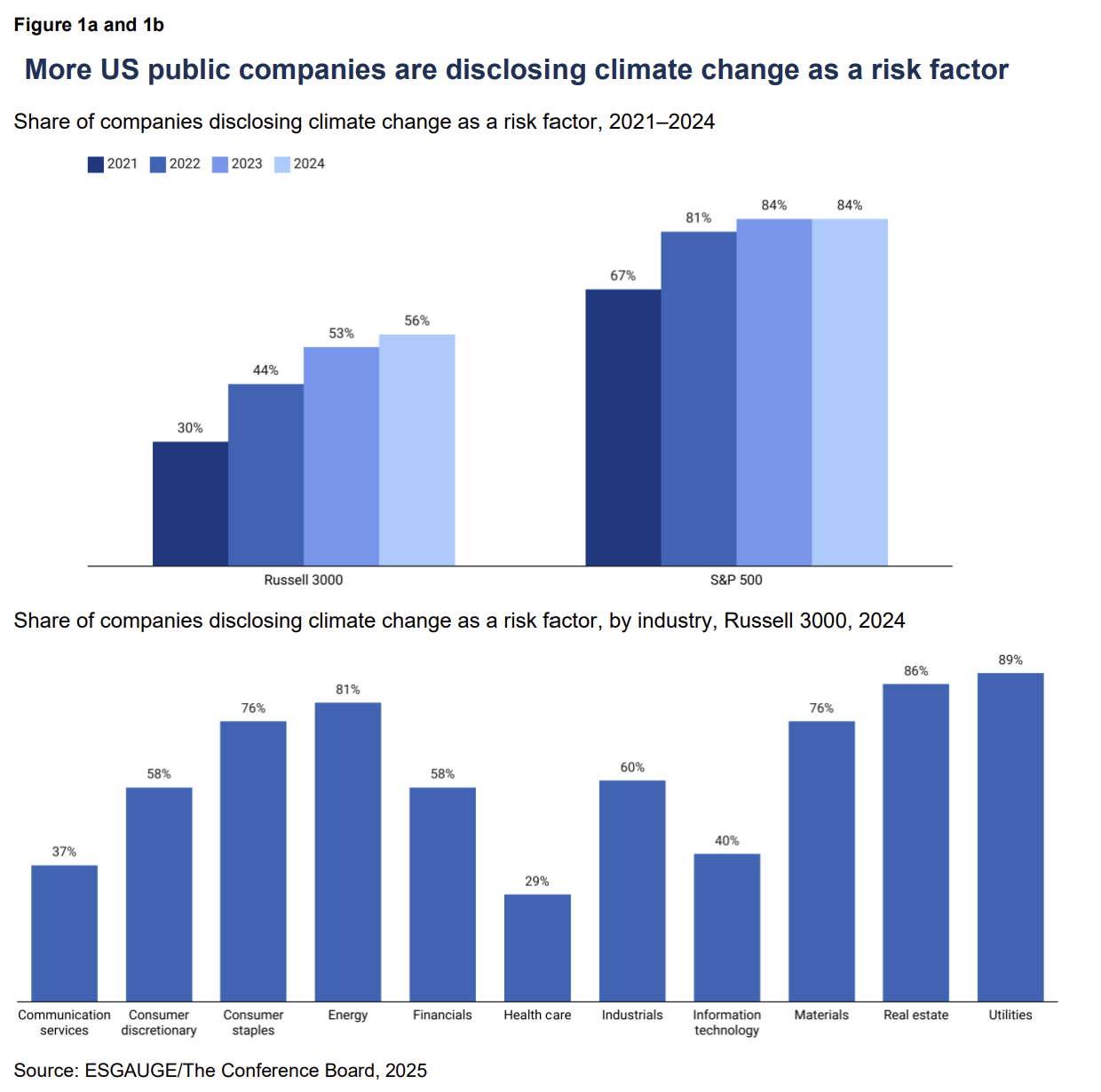

As the impact of climate-related events intensifies, more US public companies are disclosing climate change as a risk factor (Figure 1a), though not all deem it financially material. Disclosures have also become more structured and aligned with the Task Force on ClimateRelated Financial Disclosures (TCFD), which offers a framework for reporting on climate risks across four pillars: governance, strategy, risk management, and metrics/targets. [1] In 2024, 42% of Russell 3000 companies and 84% of S&P 500 companies aligned with TCFD—up from 17% and 62%, respectively, in 2021.

Sectors such as utilities, energy, real estate, materials, and consumer staples are most likely to disclose climate-related risks (Figure 1b), reflecting direct exposure to asset damage, resource volatility, regulatory pressure, and stakeholder scrutiny. Sector-specific risks include:

- Consumer staples: Agricultural volatility, water scarcity, and supply chain disruptions.

- Energy: Stranded assets, regulatory shifts, carbon pricing, and the transition to renewables.

- Materials: Resource constraints, emissions regulation, and extreme weather disruptions.

- Real estate: Asset damage, rising insurance costs, and devaluation.

- Utilities: Grid vulnerability, decarbonization mandates, and infrastructure investment pressure.

Managing climate risk in an evolving regulatory and policy environment

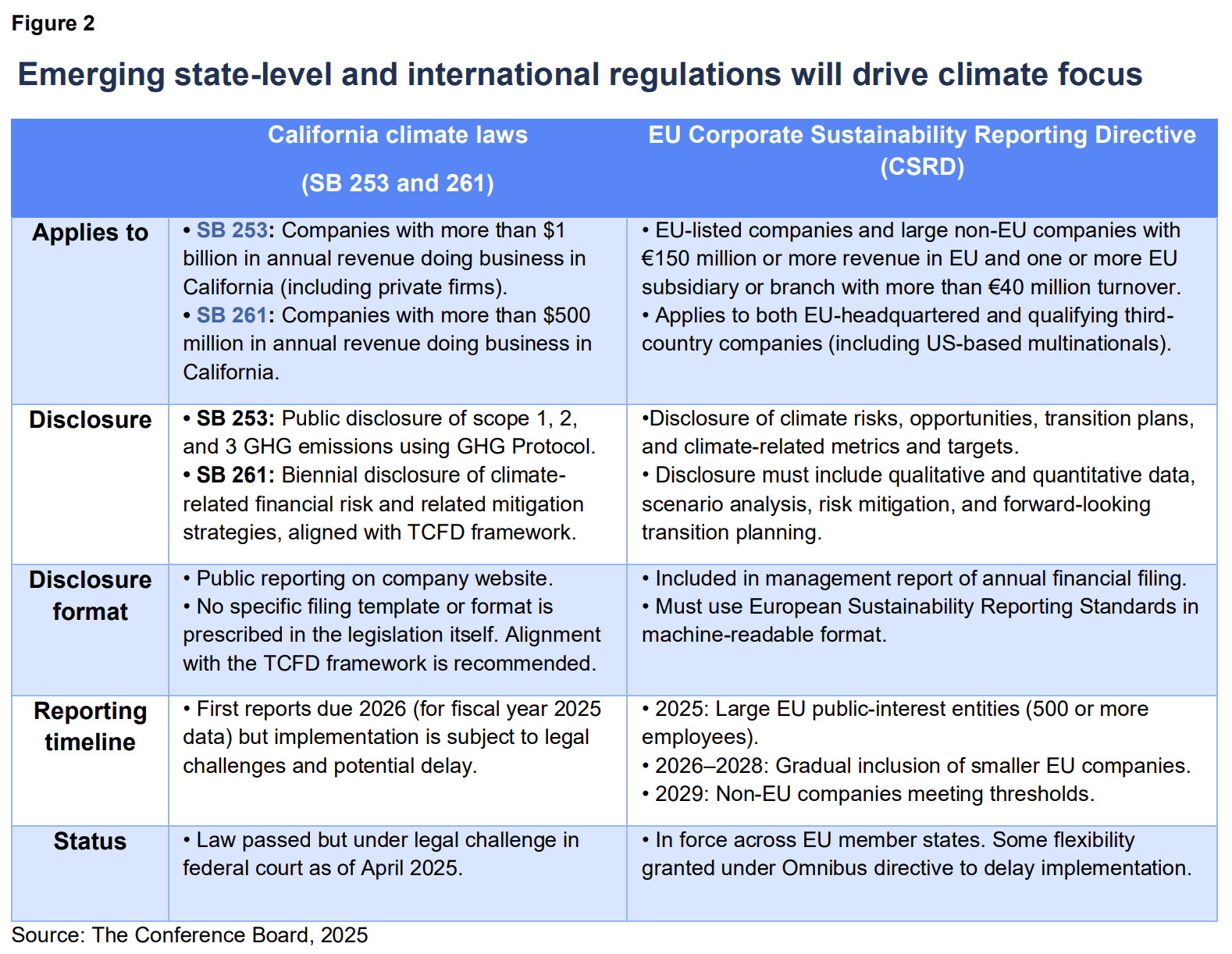

Disclosure of climate-related financial risks is expected to continue and become more standardized as regulatory mandates replace voluntary frameworks in some jurisdictions (Figure 2). In the US, California’s SB 261 will require large public and private companies to disclose climate-related financial risks and mitigation strategies in line with the TCFD framework. The EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) goes further— mandating scenario analysis, transition planning, and double materiality reporting using uniform formats. While elements of the CSRD are under review for simplification, climate risk remains central to its environmental reporting requirements.

Crucially, both frameworks—which will apply to a significant number of US companies operating domestically and internationally—reinforce that climate risk will remain a board-level issue, despite ongoing shifts in US federal policy. The current administration has moved in a sharply different direction on climate and energy, declaring a national energy emergency, expanding fossil fuel development, rolling back environmental standards, exiting multilateral climate agreements, challenging some state regulations like California’s, and deprioritizing climaterelated concerns. This growing divergence between federal, state, and international policy creates a more complex compliance landscape. However, regulatory disclosure requirements— both domestic and global—are likely to constrain any significant corporate retreat from board oversight of climate-related risks.

To further strengthen governance and reporting on climate risk, companies can:

- Anchor strategy in TCFD: Use the TCFD structure—governance, strategy, risk management, and metrics—as a baseline for internal coordination and external reporting.

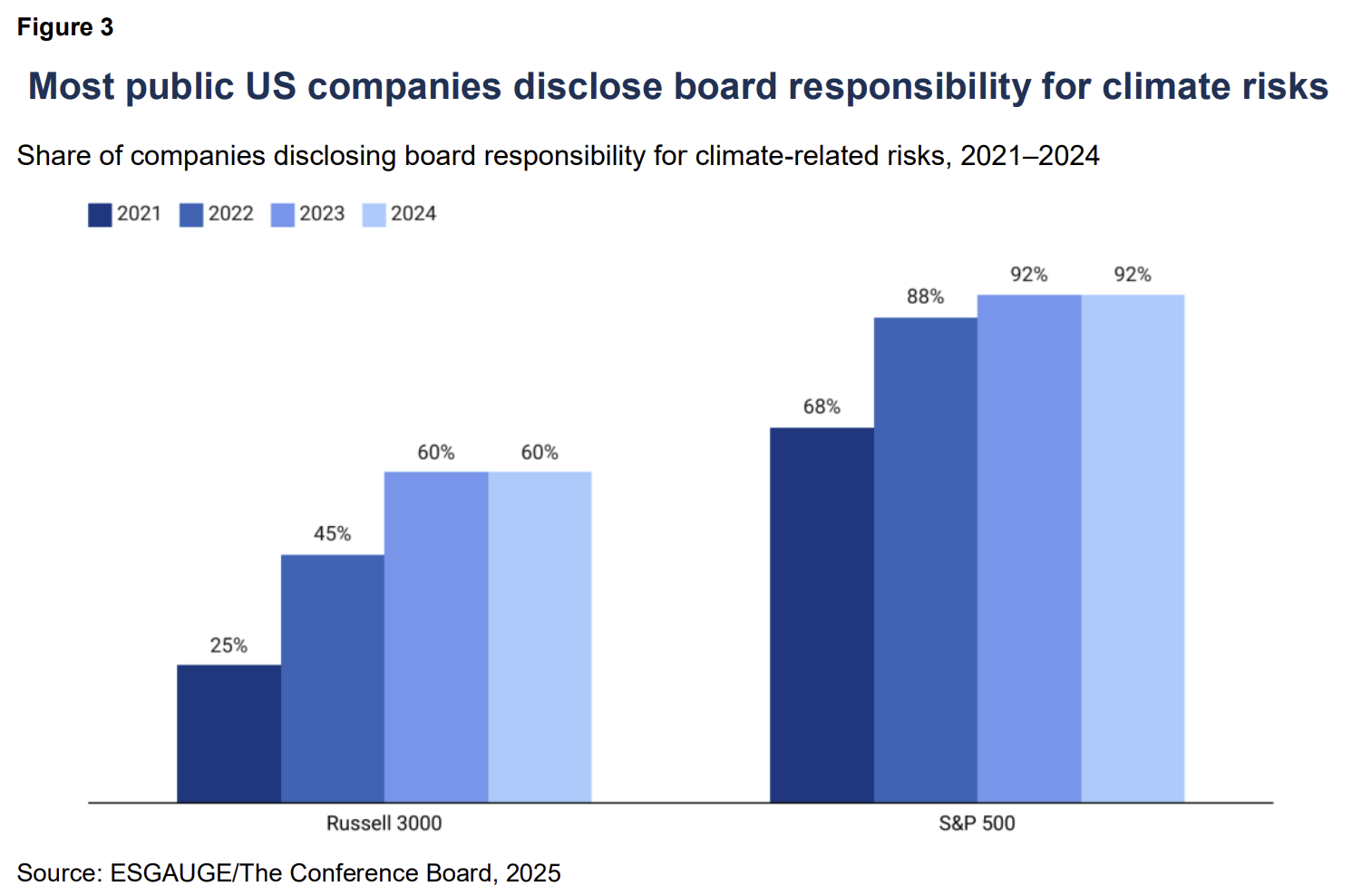

- Ensure board oversight: Assign climate risk responsibility to a board committee—typically audit, risk, nominating/governance, or sustainability—and integrate scenario analysis into enterprise risk reviews. Most US companies now disclose board-level oversight (Figure 3).

- Embed climate in enterprise risk management: Treat climate as a core business risk, updating exposure assessments and mitigation plans regularly.

- Manage legal and reputational exposure: Ensure climate risk disclosures are supported by verifiable data, clear documentation, and legal review to limit liability.

GHG Emissions: Disclosure and Mitigation

GHG emissions disclosure

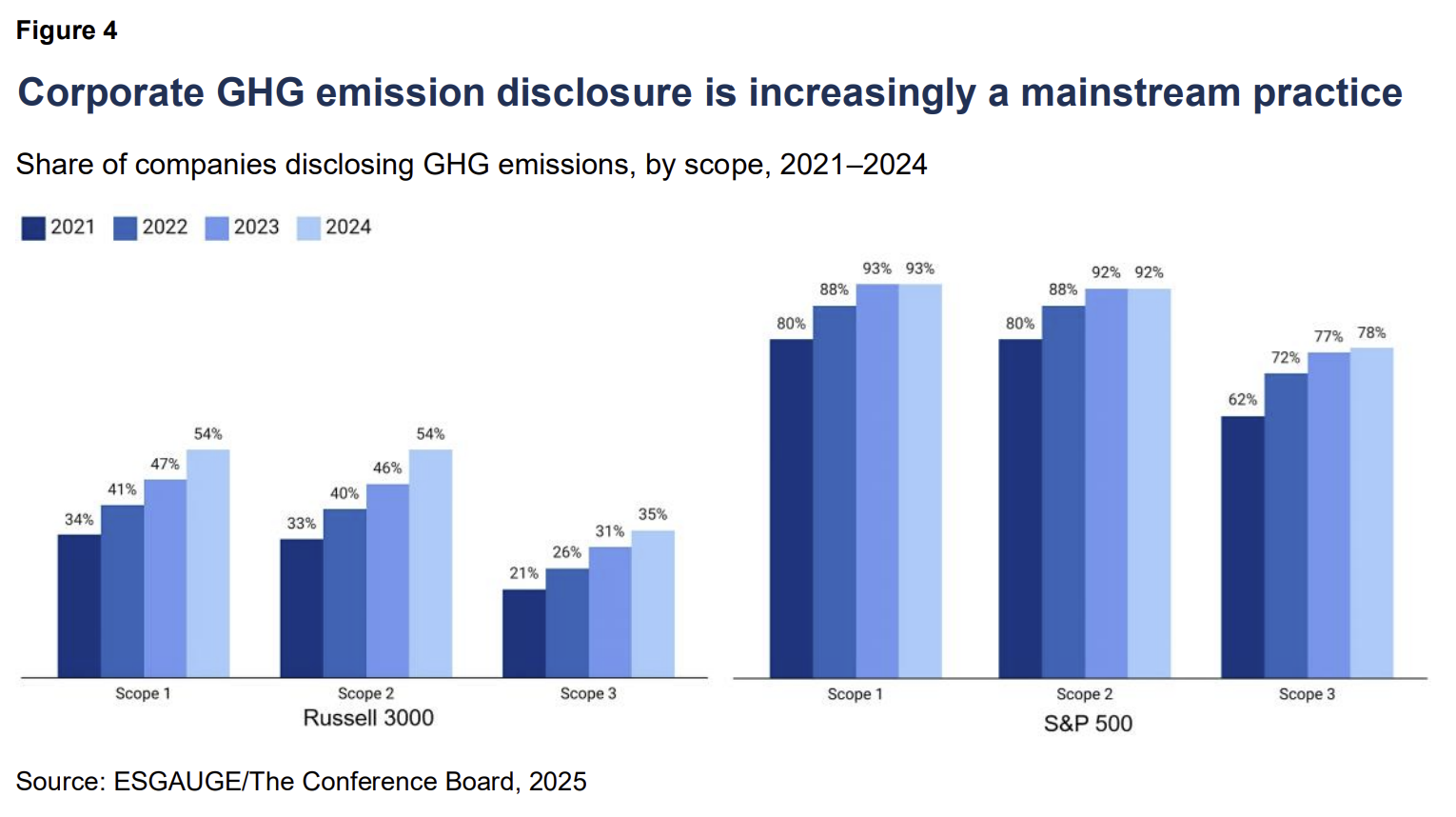

As of 2024, 93% of S&P 500 companies disclose scope 1 emissions and 92% disclose scope 2 emissions (Figure 4). Disclosure in the broader Russell 3000 remains lower—54% for both scope 1 and 2—despite meaningful gains since 2021. Scope 3 disclosure lags but is rising, reflecting mounting regulatory and stakeholder pressure for comprehensive emissions transparency. The rise in scope 3 reporting is particularly notable given its complexity and reputational sensitivity, signaling growing readiness for compliance with regulatory mandates.

Progress on addressing scope 1 and scope 2 emissions

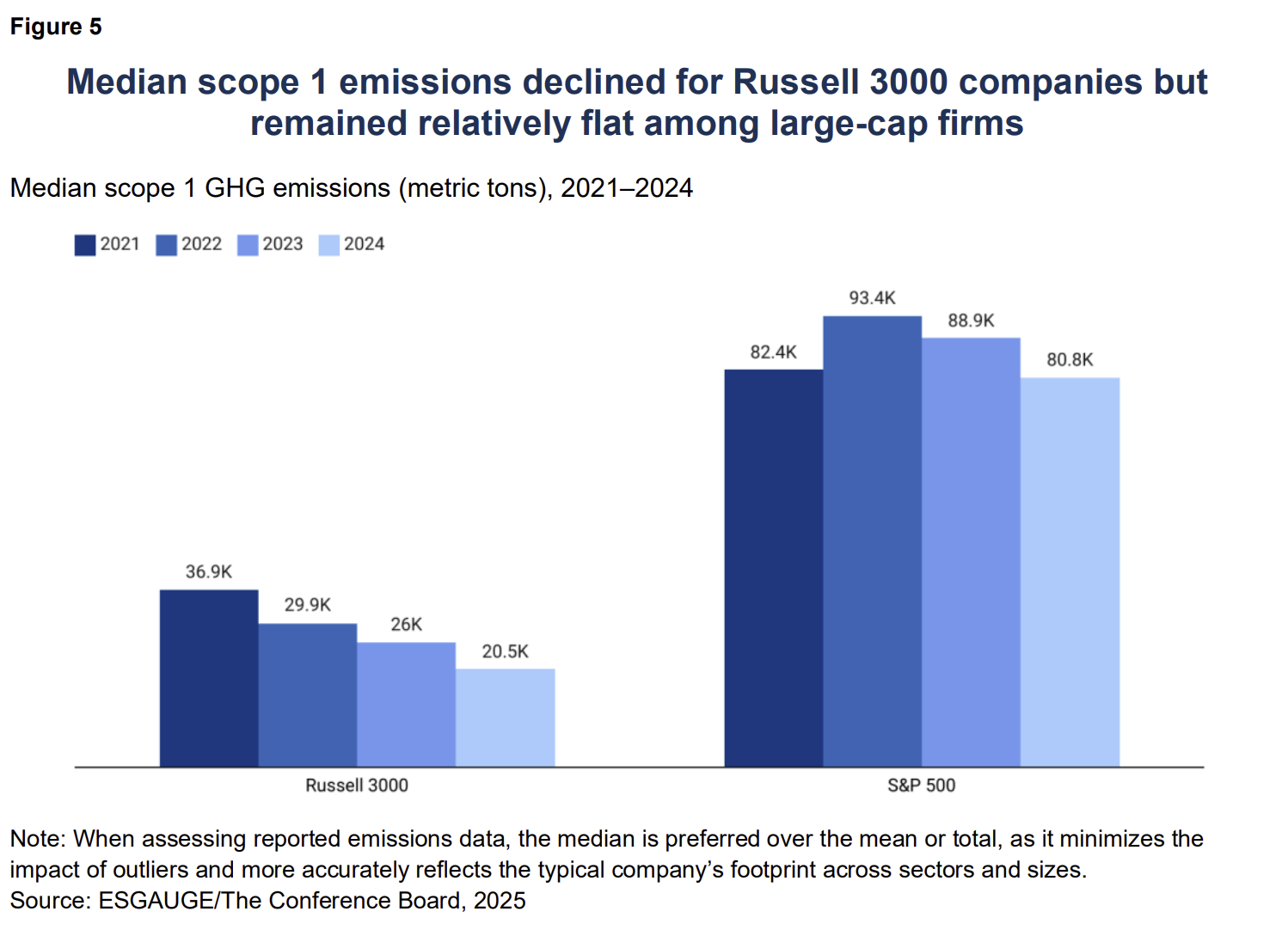

Russell 3000 companies have made significant progress on managing scope 1 emissions, with median emissions down 44% from 2021 to 2024. S&P 500 firms show a flatter trend, with a 13% decline from a 2022 peak (Figure 5). The sharper drop in the broader index reflects gains among smaller, less emissions-intensive firms, while the S&P 500’s plateau likely reflects its concentration in carbon-heavy sectors—energy, industrials, utilities, transportation, and materials—that accounted for 96% of reported median scope 1 emissions in 2024. Decarbonizing these sectors requires long-term, capital-intensive investments and still-maturing technologies. Operational growth may also have offset efficiency gains for many larger firms, keeping absolute emissions steady.

To sustain and accelerate scope 1 reductions, including in hard-to-abate sectors, companies can:

- Integrate decarbonization into core operations: Embed emissions reduction into plant upgrades, logistics planning, and asset management. Align targets with capital expenditure cycles and assign accountability to business units, not just sustainability teams.

- Track emissions intensity, not just absolutes: In sectors with rising output (e.g., steel, cement, chemicals), absolute reductions may be limited. Use intensity metrics (e.g., per ton, unit, or dollar) to reflect efficiency gains.

- Localize abatement strategies: Tailor emissions reduction plans by facility and geography, accounting for local grid carbon intensity, regulations, and available technology.

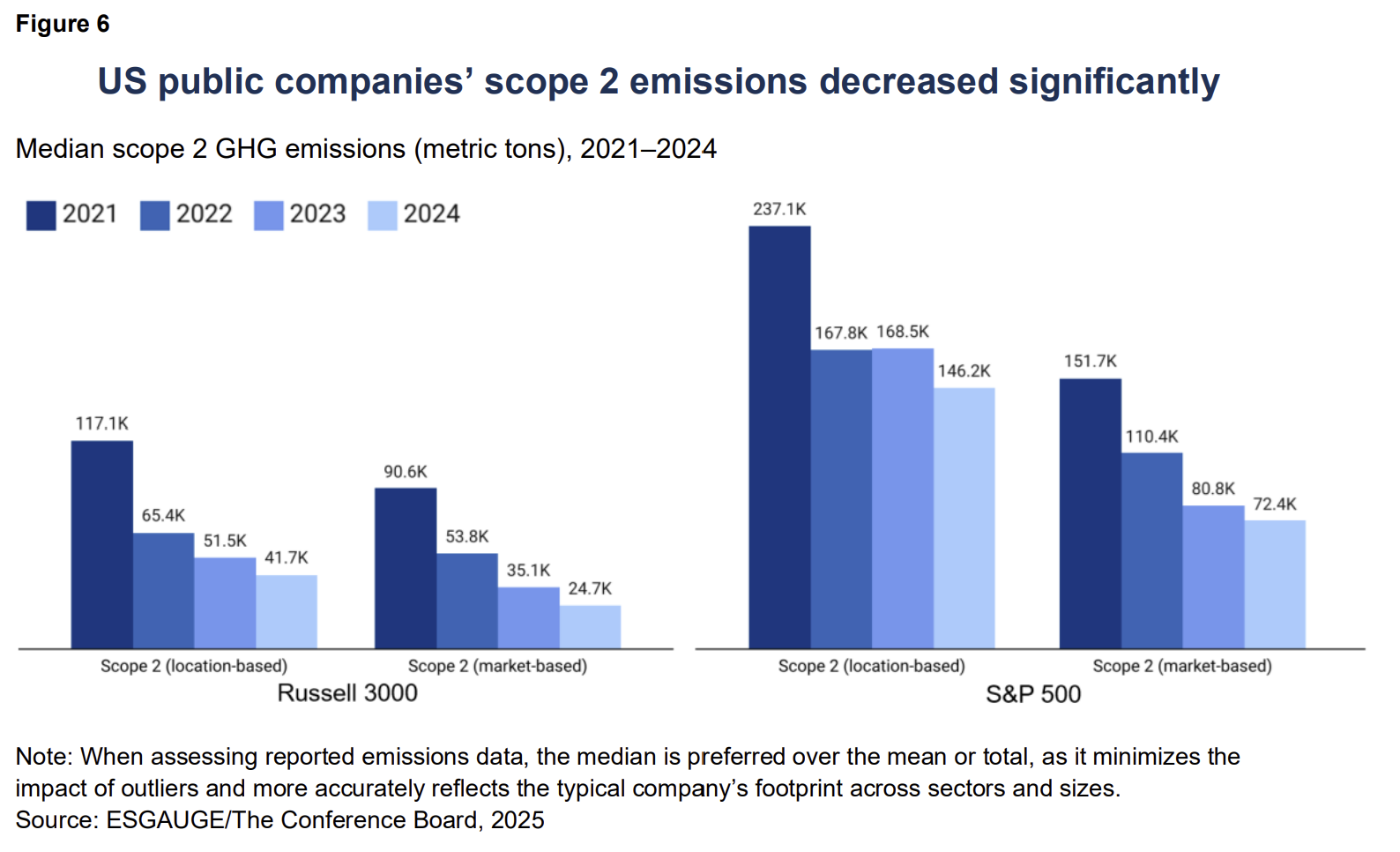

Median scope 2 emissions have dropped sharply across the Russell 3000 and S&P 500 for both location-based (down 64% and 38%, respectively) and market-based (down 73% and 52%) emissions. These are significant reductions given the scale of corporate energy use, driven by:

- Grid decarbonization (location based): Emissions have dropped across most US grids due to coal retirements, growth in renewables, and displacement by natural gas—allowing companies to benefit passively even as electricity use remained steady or grew.

- Renewable energy procurement (market based): Companies have lowered emissions via renewable energy purchases, power purchase agreements, and green utility efforts.

- Efficiency gains: Upgrades to lighting, heating, ventilation, and air conditioning; building systems; and industrial equipment have contributed to lower energy intensity and reduced emissions.

Progress on addressing scope 3 emissions

Scope 3 emissions—indirect emissions across a company’s value chain—often represent the largest share of total corporate emissions. The GHG Protocol breaks scope 3 into 15 categories, including upstream sources such as purchased goods and services, capital goods, fuel- and energy-related activities, transportation, and business travel; as well as downstream emissions from use of sold products, end-of-life treatment, and investments. Measuring these emissions is difficult due to limited supplier data, inconsistent methodologies, and dependence on proxies or industry averages. Verification is similarly challenging, particularly across complex, global, and multi-tiered supply chains.

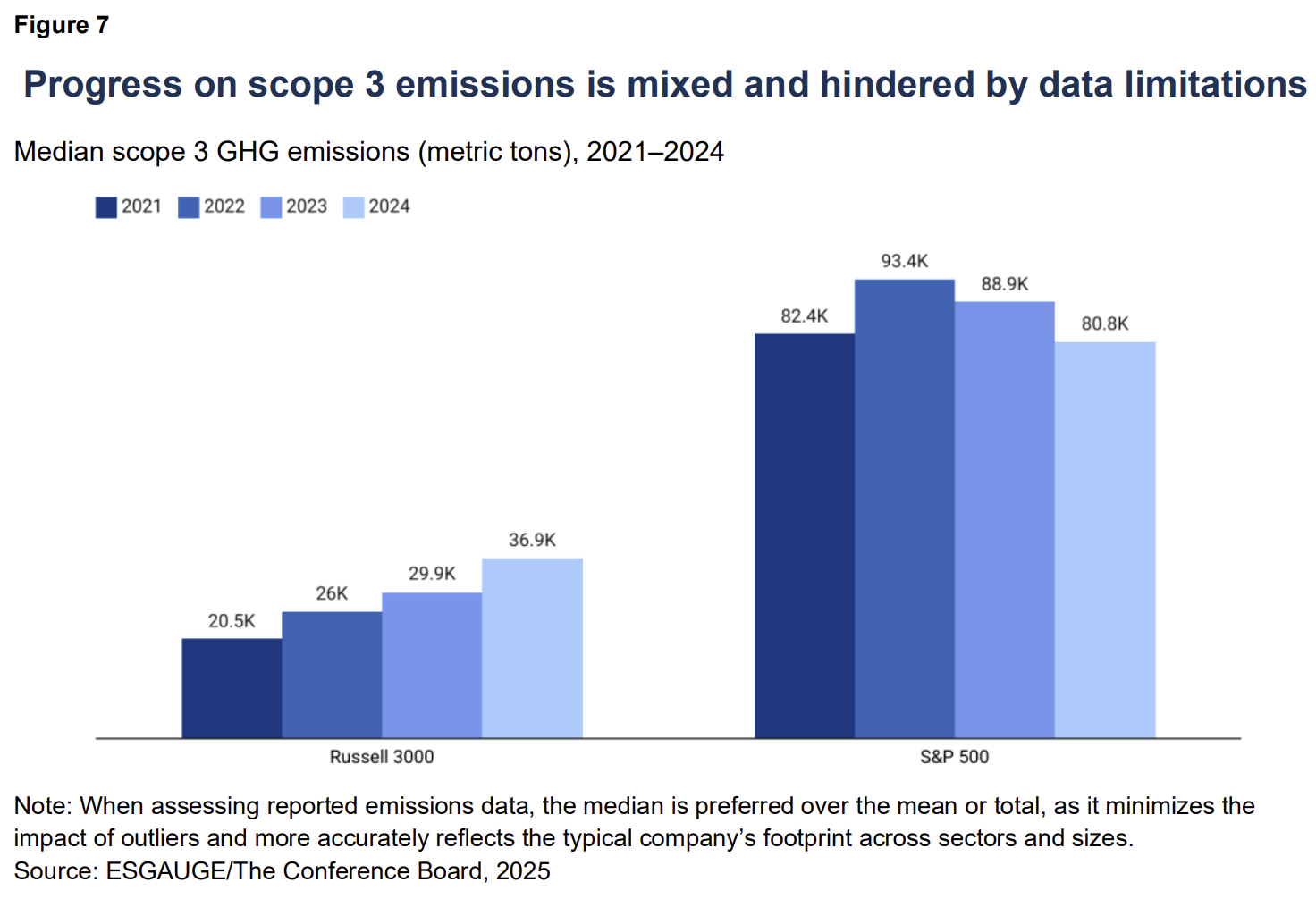

At face value, median scope 3 emissions have risen among Russell 3000 companies but declined slightly for the S&P 500 (Figure 7). However, the increase among smaller and midsized firms may reflect expanded disclosure, improved estimation methods, and broader category coverage rather than actual emissions growth. Conversely, the relative stability in S&P 500 data may signal more mature reporting systems or consistent assumptions—though underreporting remains a possibility.

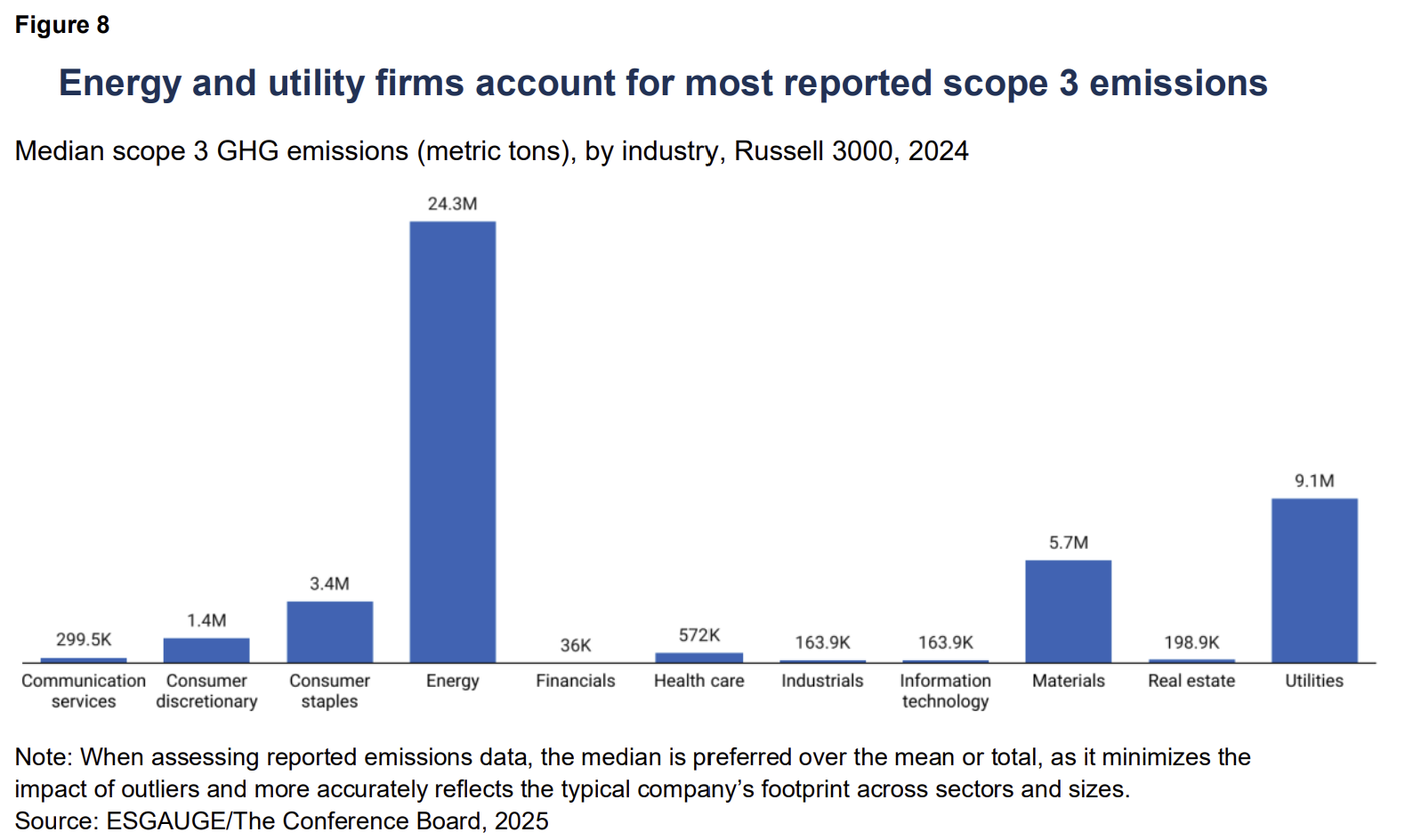

Industry-level variation is also significant. The energy sector far exceeds others in scope 3 emissions (Figure 8), driven by downstream use of sold products, while sectors such as manufacturing, consumer goods, and financial services face unique exposures tied to supply chains, product design, and financed emissions.

As methodologies improve and regulations mandate broader scope 3 disclosure with external assurance, data quality and comparability will continue to advance. Notably, companies are already revising figures based on new methods—Novo Nordisk’s 2024 CSRD report, for example, halved its previously reported 2023 scope 3 emissions after recalculating estimates using an improved methodology.

To strengthen scope 3 emissions management and reporting, companies can:

- Prioritize material categories: Focus on one to three key categories (e.g., purchased goods, transportation, product use) that account for the majority of emissions and where influence is feasible.

- Improve data granularity: Shift from high-level estimates to supplier-specific data. Build systems to collect and validate data through procurement, contracts, and product design.

- Engage suppliers: Provide tools, training, and incentives to help suppliers calculate and report accurate emissions data.

- Standardize internally: Apply consistent methodologies across business units and geographies using the GHG Protocol and relevant industry guidance.

- Plan for recalculations: Transparently disclose methods, assumptions, and data gaps. Treat restatements as part of accuracy improvements, not as setbacks.

- Align with global frameworks: Harmonize internal reporting with regulatory expectations and emerging global standards, anticipating that US rules may lag but global pressure will intensify.

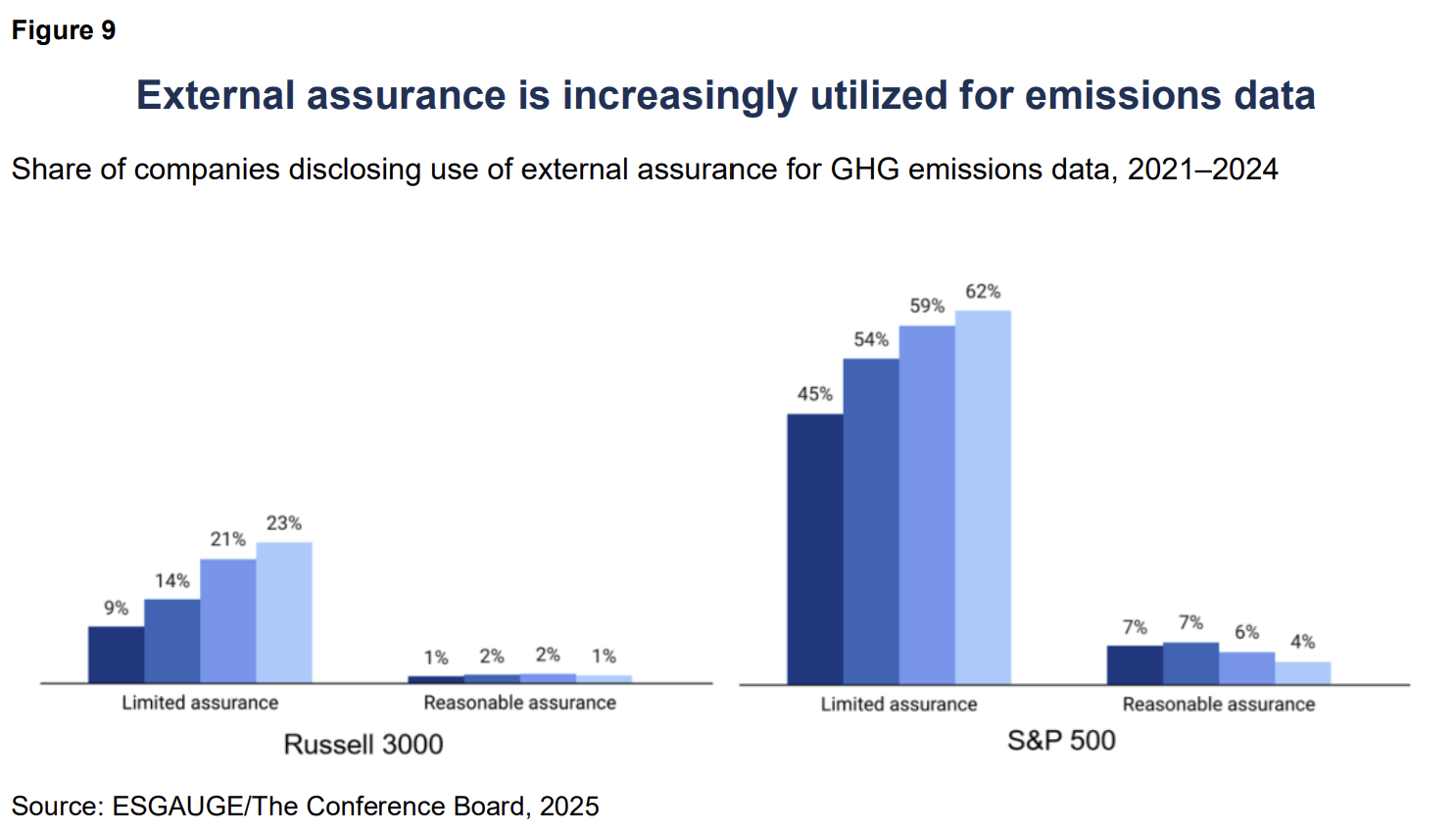

External assurance of GHG emissions data

As climate disclosures expand and regulations tighten in some jurisdictions, more companies are using external assurance to validate emissions data (Figure 9). This process involves an independent third-party review of data for accuracy, completeness, and alignment with standards such as the GHG Protocol. “Limited” assurance provides moderate confidence based on a high-level review, while “reasonable” assurance offers higher confidence through more indepth testing. While not yet common, reasonable assurance will be required for scope 1 and 2 emissions under California’s climate laws starting in 2030. In the EU, current CSRD proposals would retain limited assurance without mandating a shift to reasonable assurance.

To utilize external assurance efficiently and effectively, companies can:

- Start with limited assurance for scope 1 and 2: Build internal readiness before expanding to scope 3 or pursuing reasonable assurance.

- Align sustainability reporting with financial audit processes: Leverage internal audit and finance teams to apply controls, documentation, and oversight similar to financial data.

- Prioritize material metrics: If full assurance is not feasible, focus on high-impact disclosures such as enterprise-wide GHG emissions, energy use, and reduction targets.

- Engage assurance providers early: Define scope, data requirements, and timelines in advance to minimize rework and reduce costs.

- Disclose assurance accurately: Identify the assurance provider, scope, level, and applicable standards (e.g., ISAE 3000, AA1000AS) for transparency and comparability.

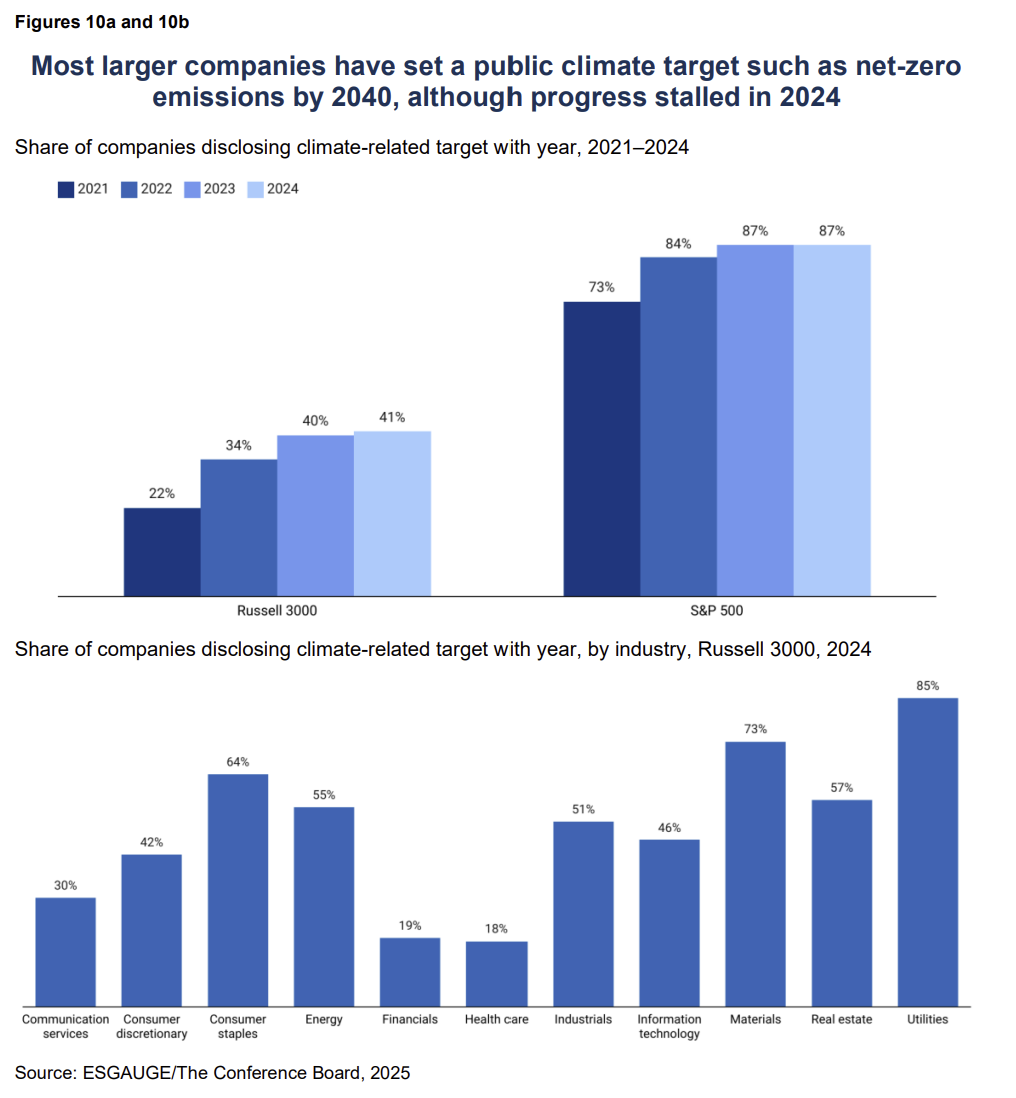

Climate Targets and Goal Setting

As emissions disclosure matures, more companies have publicly set climate-related targets, such as carbon neutrality or net-zero commitments. Target setting varies significantly by sector, driven by differences in regulatory exposure, investor pressure, emissions intensity, and operational readiness. The highest disclosure rates are found in utilities and materials— industries with high scope 1 emissions, clear regulatory pathways, and direct ties to decarbonization.

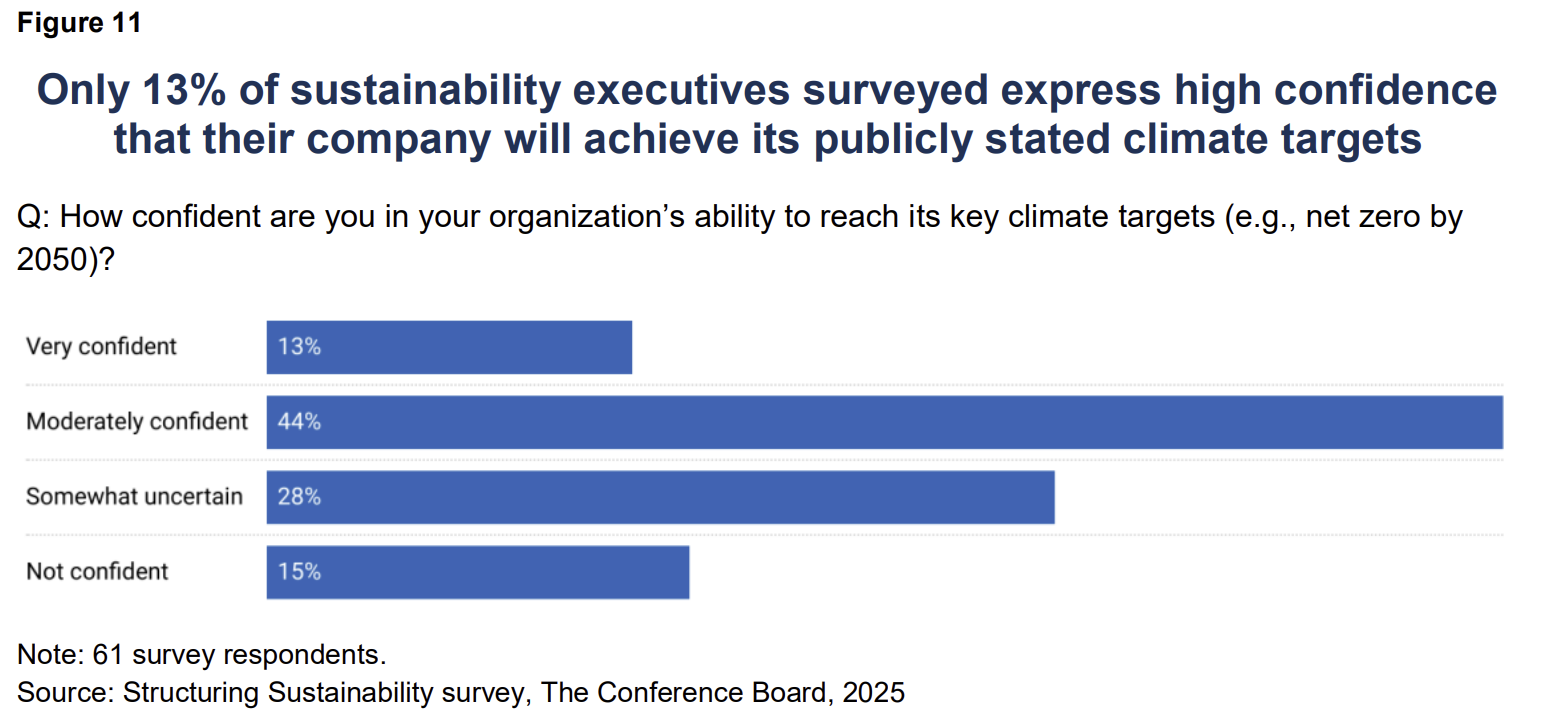

However, the pace of new climate target disclosures has slowed, signaling a plateau in voluntary commitments. At the same time, the median target year has steadily shifted later— from 2030 in 2021 to 2035 in 2024. A recent survey by The Conference Board found that only 13% of sustainability leaders are very confident in meeting their key climate goals, while 43% express uncertainty or doubt (Figure 11).

Contributing factors to declining confidence include:

- Feasibility concerns: Many early targets were set without fully assessing operational, technological, or financial constraints. As implementation progresses, some companies are revising or narrowing targets to reflect practical realities.

- Litigation and greenwashing risk: Long-term targets now carry greater exposure, with increasing scrutiny from regulators and potential lawsuits from shareholders or activists.

- Environmental, social & governance (ESG) backlash: The politicization of ESG, particularly in the US, has made public climate commitments riskier, especially for mid-sized and consumer-facing companies.

- Shifting investor focus: Some investors now prioritize operational performance over public pledges, reducing the incentive to set ambitious goals without credible delivery plans.

Going forward, companies can consider moving from broad, long-term pledges to credible, transparent, and actionable targets. This includes setting interim milestones with accountability, backed by decarbonization roadmaps, business-unit alignment, and strong governance. The Science Based Targets initiative offers a framework for aligning goals with climate science.

Companies should also proactively engage stakeholders—including regulators, investors, and civil society—to communicate how targets are being implemented and adjusted, not just announced. This transparency will be key to building trust, mitigating legal risk, and maintaining credibility in an increasingly skeptical and scrutinized environment.

This article is based on corporate disclosure data from The Conference Board Benchmarking platform, powered by ESGAUGE

1 The Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), established by the Financial Stability Board in 2015, provides a globally recognized framework for climate risk reporting, structured around four pillars: governance, strategy, risk management, and metrics and targets. It has shaped voluntary disclosure practices across markets, with broad adoption by investors, companies, and regulators. In 2023 the TCFD was formally disbanded, with its responsibilities transferred to the International Sustainability Standards Board, created by the International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation to develop a global baseline for sustainability disclosure. TCFD principles are also being codified into law through emerging regulations, including California’s Senate Bill 261 and the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive.(go back)

Distribution channels: Education

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.

Submit your press release